South Dakota v. Wayfair, a landmark Supreme Court case decided earlier this year, changes the sales tax landscape for online retailers. The ruling also leaves state governments grappling with decisions about how to handle the change.

What happened?

In Wayfair, the Supreme Court ruled 5-4 in overturning precedent set in Quill Corp. v. North Dakota and National Bellas Hess, Inc. v. Department of Revenue of Ill., which established a sales and use tax nexus rule, requiring a company to have a “physical presence” within the state in order for it to be liable for the collection and remission of sales and use taxes in that state. The Court subsequently interpreted “physical presence” to mean that the company needed to employ at least one person or occupy at least one building in the state.

The idea was that companies without a physical presence in a state probably weren’t doing a significant amount of business there, and thus shouldn’t be subjected to the rigor of complying with the state’s sales tax system. Instead, the state needed to rely on the consumers themselves to pay a “use tax” on their out-of-state products—a system with an estimated four percent compliance rate among taxpayers.

The Court in Wayfair recognized that times have changed with the advent of online retail, which expanded by 16% last year. An online company can now very easily make sales in states where it doesn’t have a physical presence. Companies like Wayfair, Inc. are very aware of the advantage this affords them over brick-and-mortar stores, and Wayfair even boasts on its website, “[O]ne of the best things about buying through Wayfair is that we do not have to charge sales tax.” The Supreme Court also recognized that the Internet revolution has contributed to the revenue shortfall that states face.

Realizing that the correlation between physical presence within a state and conducting substantial business in that state has eroded as online selling has exploded onto the scene, the Supreme Court ruled that a physical presence need not be necessary in order for states to require companies to collect a sales tax.

What does it mean for retailers?

No, Amazon isn’t going to go bankrupt over this ruling. (In fact, Amazon’s physical distribution centers mean that it already collects sales tax everywhere, although third-party sellers using Amazon as a platform don’t have to.) Online retail is here to stay, but traditional brick-and-mortar sellers have won a small battle with Wayfair, which levels the sales tax playing field.

Online retailers will have to pony up the costs of compliance in states where they don’t have a presence—a task that could be made easier by agreements like the Streamlined Sales and Use Tax Agreement. Under the Agreement, more than 20 states have standardized their sales tax systems under uniform rules and definitions in order to ease compliance burdens for companies that are spread across states.

This landmark ruling also requires online retailers to consider their business models, customer and sales IT systems, financial reporting, and internal processes for calculating their tax obligations.

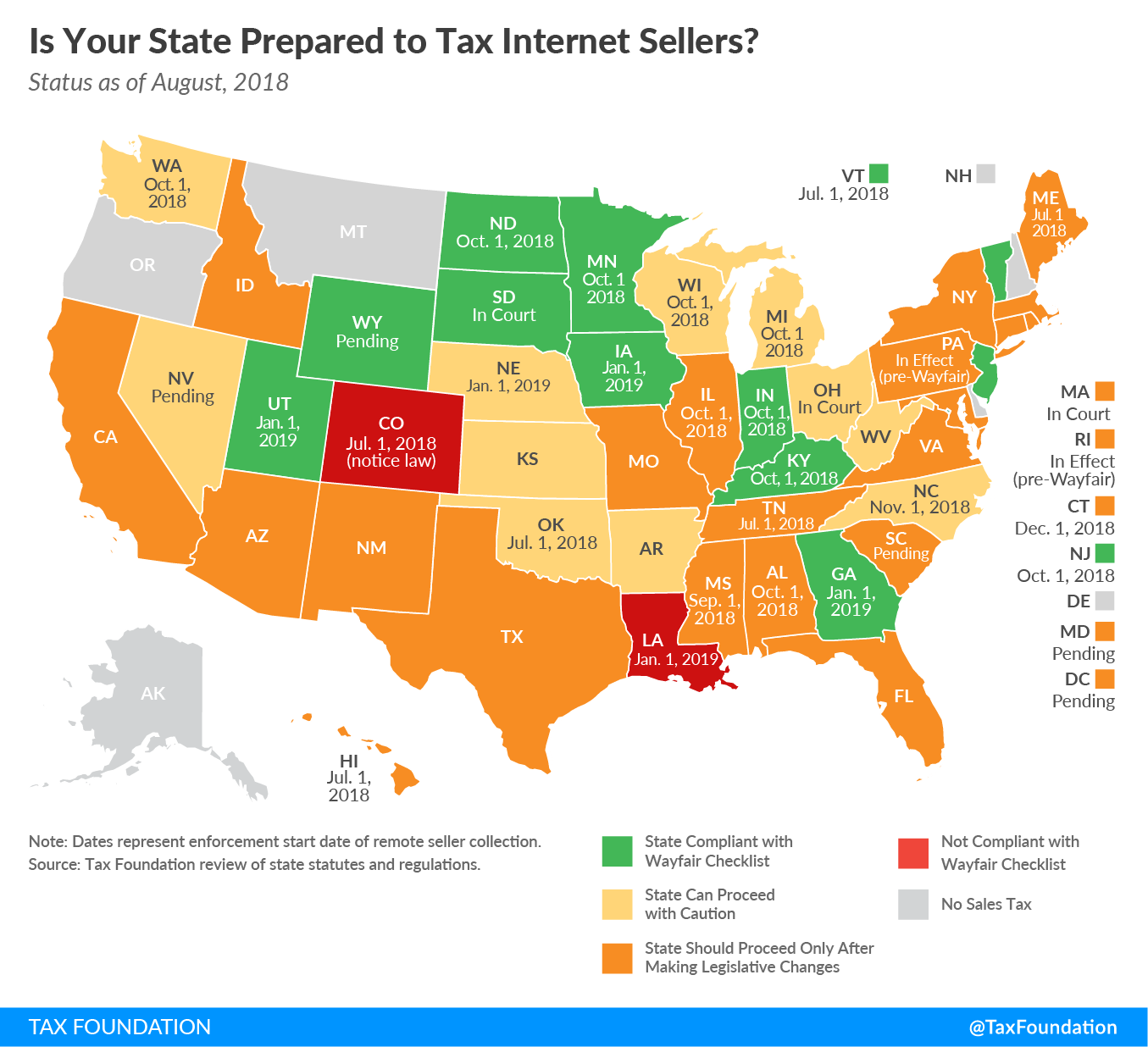

What does it mean for states?

While Wayfair does away with the physical presence requirement, it doesn’t add a new requirement in its stead. Rather, it will be up to the states to decide what constitutes “sales tax nexus” for their purposes. The Court spoke favorably of South Dakota’s proposal, which provides a safe harbor to companies who transact limited interstate business by only requiring companies to collect tax if they conduct more than $100,000 of business in the state, or conduct more than 200 separate transactions.

Other states, however, have other ideas: Massachusetts and Ohio have proposed that companies who offer mobile apps to residents or place cookies on residents’ web browsers should collect tax—a modern interpretation of “physical presence.” Alternatively, a “click through” nexus statute could require collection from companies who contract with residents to refer customers.

As states grapple with these regulatory decisions, one thing is certain: the estimated $8 to $33 billion in annual revenue that states have lost out on under Quill and Bellas Hess will soon be flowing into state coffers. This will mean different things to different states depending on how important sales taxes are to their revenue structures.

It’s no surprise South Dakota was the one to air its grievances in front of the high court—it is one of the seven states with no personal income tax, so it certainly felt a pinch before Wayfair, as more than a quarter of its state revenue came from sales taxes. In addition, because so much of South Dakota is rural, its brick-and-mortar stores were already facing an uphill battle.

Other states with no personal income tax will see the most benefit from the change: South Dakota, Nevada, Washington, Texas, and Florida are five of the 12 states where sales tax accounts for more than a fifth of government revenue. Meanwhile, New Hampshire, Delaware, Montana, and Oregon, who don’t collect regular sales taxes at all, will not see a change.