Update: if you found this article helpful, you might also be interested in the March 19th article in MedPageToday, “Social Determinants of Health an ‘Urgent Issue’.”

It seems you can’t read a story about healthcare these days without references to social determinants of health. To pick a recent example, healthcare technology company, Change Healthcare, made a bit of a social media splash recently when it reported findings from its eighth annual survey of payers, with a smattering of providers, consultants, and other healthcare ecosystem partners in the survey pool.

The headline that grabbed attention? “80% of Payers Aim to Address Social Determinants of Health.” At one level, this shouldn’t be news; the connections between individual behaviors and health status have been understood for decades. What has evolved over more recent years, however, is our understanding of the substantial influence that factors outside of healthcare have on our length and quality of life.

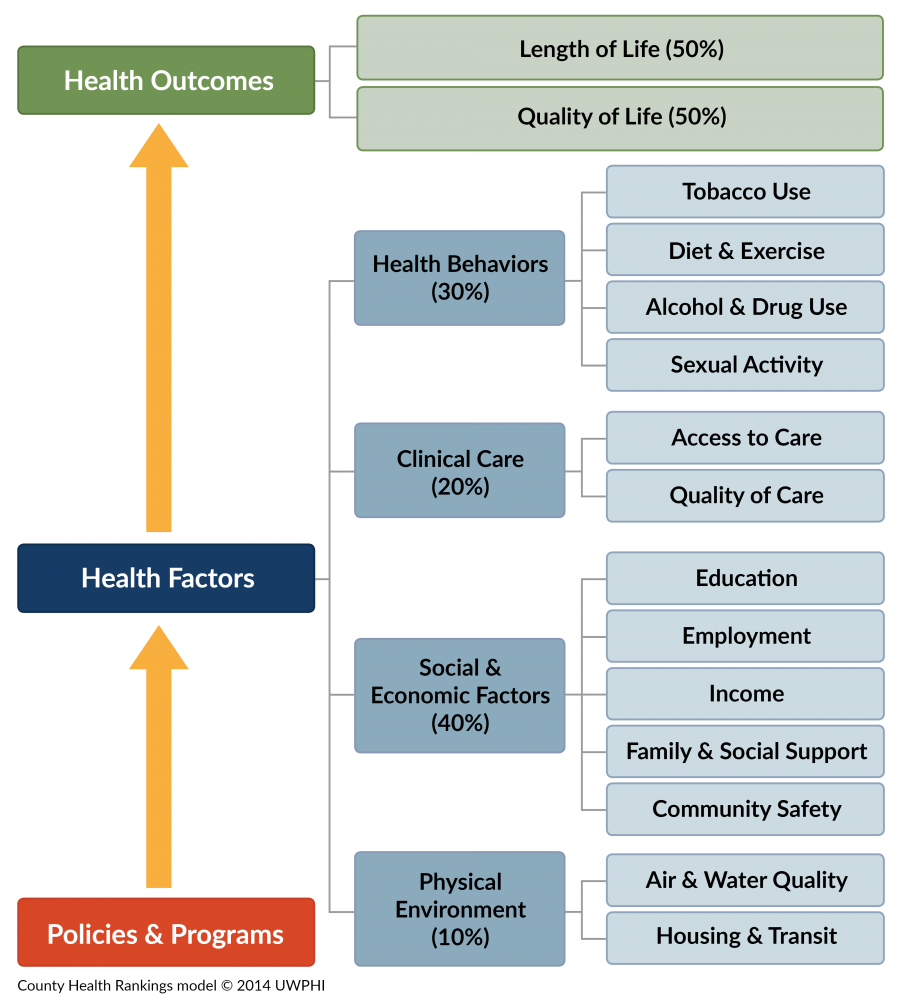

My former colleagues at the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute, in a long-standing collaboration with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, have distilled this science into an accessible visual that illustrates the point:

United Healthcare, Gundersen Health System, and Housing

United Healthcare, Gundersen Health System, and Housing

Since 2011, United Healthcare has invested $350 million in affordable housing projects in 14 states, according to the Milwaukee Business Journal. That includes more than $30 million in investments in housing in Milwaukee and Madison.

Why? Because United Healthcare is a major player in Medicaid managed care, and homelessness and living in substandard housing are well-known contributors to poor health and higher healthcare costs. By investing in housing, United Healthcare is banking on improved health, reduced healthcare utilization, and improved profitability. United Healthcare’s strategy demonstrates clearly the impact that social determinants of health can have.

At a recent briefing on Housing and Health at the Wisconsin State Capitol, United Healthcare leaders shared data demonstrating that people living in supportive housing (housing combined with case management and access to other needed social services) saw a 46% reduction in emergency department usage, and a 51% reduction in both ambulance trips and hospital bed days, in just one year.

United Healthcare’s commitment is also an example of the shared value strategy of investing in community conditions that make United Healthcare’s underlying business – health insurance, especially Medicaid managed care – more profitable. Businesses need many partners, and often engagement with government, to drive meaningful impacts on community conditions, and United Healthcare has tapped public and private sector partners to advance its work.

At this same briefing, Sandy Brekke with Gundersen Health System discussed Gundersen’s work in collaboration with many partners through the La Crosse Collaborative to End Homelessness, in La Crosse by focusing first on homeless veterans, then other chronically homeless adults, and most recently families with children. Brekke highlighted the dollars and cents reasons that a health system might choose to invest in upstream, preventive strategies like housing. According to an analysis produced by the Economic Roundtable in 2012, the annual cost of a homeless person to many public and private sector systems – healthcare, human services, criminal justice – is nearly $64,000 annually, while the annual system costs for a person in permanent housing with supportive services is just under $17,000. So, $1 invested in supportive housing can avoid nearly $3 in health, human services, and law enforcement expenditures. More evidence that housing and health are directly linked, and that prevention pays.

Humana and Bold Goal Communities

For its part, another national health insurer, Humana, is continuing to expand its Bold Goal initiatives in metropolitan areas around the U.S. With an enhanced focus on non-medical health determinants including food insecurity and social isolation, Humana is building cross-sector coalitions in each of these communities and focusing attention on a reliable but hard-to-influence measure of health: how people say they feel.

Humana’s goal is to drive a 20% increase, by 2020, in the number of physically and mentally “healthy days” its health plan members and employees report experiencing. Specifically, Humana tracks community members’ responses to the following two questions, which have been asked by the CDC since 1993:

- Thinking about your physical health, which includes physical illness and injury, for how many days during the past 30 days was your physical health not good?

- Thinking about your mental health, which includes stress, depression and problems with emotions, for how many days during the past 30 days was your mental health not good?

Humana has found that these indicators have improved, and clinical outcomes for Humana Medicare members have also improved, in four of the seven original Bold Goal Communities.

What is good about this work beyond these results, however, is that it represents a shared value strategy that has Humana investing not only in communities where its health plan members live, but also in its own workforce. Humana’s employees’ healthy days are up 18% over the first five years of this effort. Not only that, Humana also saw improvements in employee engagement and retention scores, results that Humana attributes in part to employees’ alignment around the sense of company purpose expressed in the Be Bold initiatives.

So here’s what we know:

- Investing in the other drivers of health, beyond healthcare services, yields real improvements in quality and length of life and real returns to the bottom line.

- Making this work sustainable and effective requires leadership, patience, and partnerships with public and private sector organizations.

- Connecting employees to your company’s positive societal impact is good for business. That’s shared value in a nutshell.